To forestall heat deaths, bolster our health data

Delayed Monsoons to Deadly Heatwaves: India’s Battle with Extreme Weather

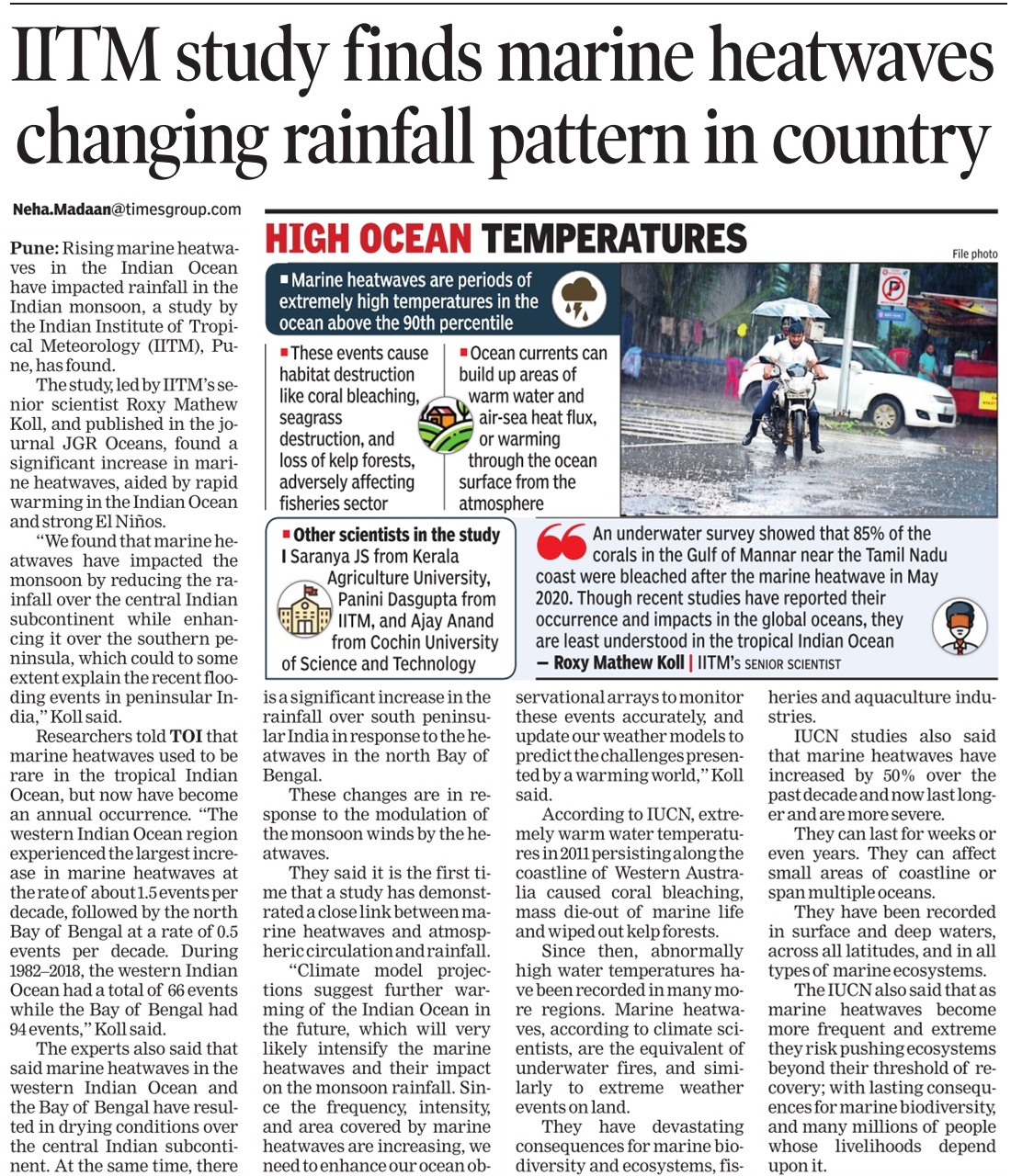

India witnessed a cascade of severe weather events during the last couple of weeks. A delayed monsoon stalled in the south, a severe cyclone landing in the northwest, and heavy rains and floods in the northeast. The rest of the country was hit by scorching heatwaves. Maximum temperatures over central and north India shot up by 5–6 degrees Celsius above normal during the last few days.

These severe weather events come with a cost. The sluggish monsoon has led to delays and uncertainty in the sowing of crops. The cyclone in the northwest and floods in the northeast have displaced thousands of people and resulted in several deaths and loss of property and houses. The extreme heat has led to several deaths and affected the health and well-being of a large population across the states in north and east India.

Sequence of weather events

All these seemingly independent weather events are interlinked. The atmosphere is a sea of floating air over the globe. Perturbations in the air in one place lead to weather changes in another place. To start with, an early El Niño, characterized by warm waters in the Pacific, weakened the trade winds and delayed the monsoon onset over India. Weak monsoon winds along with an exceptionally warm Arabian Sea made it favorable for the formation of Cyclone Biparjoy.

Cyclones lead to rising moist air convection and cloudy sky where it forms, but results in hot dry air sinking and clear sky over large swathes of land nearby. This time, Cyclone Biparjoy formed close to the time when the monsoon was setting in and took the monsoon moisture away with it. This led to the central and north Indian states hitting a 70–80% deficit during the first twenty days since the start of June. The dry hot air accumulating, clear skies that bring in more of the sun’s heat, and the rainfall deficit led to scorching hot days.

Link to climate change

Now due to climate change, additional heat gets accumulated during these events, resulting in more intense heatwaves. The El Niño—that triggered the sequence of events here—is also getting stronger as oceans absorb more than 93% of the additional heat from global warming. It is, hence, no surprise that the flurry of extreme weather coincided with the global average surface temperatures temporarily crossing 1.5 degree Celsius during early June.

While carbon emissions continue unabated and the globe warms, the Indian subcontinent is one place that is worst hit. Heatwaves are projected to become more frequent and intense in the future, posing a threat to the growing vulnerable population in the region. In fact, future climate projections indicate a six-fold rise in heatwaves over India by 2060, by the time the global average temperature rise crosses 2 degrees Celsius.

Geographically, the heatwave zone lies diagonally across the Indo-Pak region. The area covered by heatwaves are now expanding with climate change. In India, the states of Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Delhi, Haryana, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh and Telangana lies in the heatwave zone.

Forecasts and disaster management

Efficient forecasts and disaster management at ground have reduced the number of deaths due to cyclones and floods. The mortality rate of tropical cyclones reduced by 94% in the past two decades, while that of floods has reduced by 49%. This is evident if we compare the 1998 Gujarat cyclone and the 1999 Odisha cyclone which killed tens of thousands of people, with the cyclones in the recent period that caused deaths in two-digit numbers. This is even though the number and intensity of cyclones have increased drastically in the Arabian Sea. Though economic and infrastructure loss is still high for cyclones, the reduction in the number of deaths is a huge success story for India.

This is not the case for heatwaves though. An assessment by the Ministry of Earth Sciences of the mortalities due to extreme weather events in India shows that the mortality rate due to heatwaves has increased by 62% in the past two decades, in response to a 138% increase in heatwaves. Heat waves used to be the third most severe weather event responsible for mortalities after floods and cyclones, but have now become the second most disastrous event.

To address this growing crisis, the government has initiated measures to mitigate the impacts of heatwaves. After the deadly heat waves in 2010, Ahmedabad came out with the first heat action plan, which has been taken up by several other cities now. These heat action plans include early warning systems based on forecasts, public awareness campaigns, and other efforts like cooling centers, accessible drinking water, etc. Definitely, this needs to be expanded to all heatwave-prone areas.

Way forward

What can we do to reduce the heatwave-related deaths and health impacts? The first step is to acknowledge the fact that heatwaves are now an annual affair from February to June, and are going to intensify further in the future. The next step is to assess hotspots where heatwaves are on the rise and identify the vulnerable communities that need targeted assistance for building heatwave resilience.

There is an urgent need for policies that prioritize ecosystem-based urban scaping that can keep cities and towns cool, architecture and building codes that keep our indoors cool at work and home, and improved healthcare infrastructure fostering community resilience. Regardless of how the long-term policies unfold, if you are caught in a heatwave anytime, the most important advice would be to stay indoors, reduce physical activity, and try to keep your body cool and hydrated with water.

To forestall heat deaths, bolster our health data

Mortality due to heat waves is very high in Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Odisha. Long-term climate data is available to identify local heatwave hotspots within the states so that we can prepare precautions and policies customized for each locality. Though climate data is publicly available and accessible, health and mortality data are scattered and underreported. It is a struggle to obtain health data even for research purposes.

On average, about 350 deaths per year are directly attributed to heatwaves. This is often an underestimation because the mortality data here accounts only for the fatalities directly from heatwaves, usually due to heatstroke for outdoor workers. Indirect deaths due to existing ailments aggravated by heat, and deaths that might have occurred later are not counted.

It is possible to predict climate-sensitive diseases and heat-related incidences well in advance, by training forecast models with the past climate and health data. The same strategy can be used to foresee the potential changes in heat-related health impacts for the next few decades since we have an idea of how the overall climate is going to change in the future. These predictions can save lives and livelihoods but are feasible only if we have access to health data.

— Roxy Mathew Koll is a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology and a lead author and reviewer of recent IPCC reports.

Originally published in the Hindustan Times [PDF]

Suggested Citation:

Roxy M. K., “To forestall heat deaths, bolster our health data.”, Hindustan Times, 22 June 2023, p14.